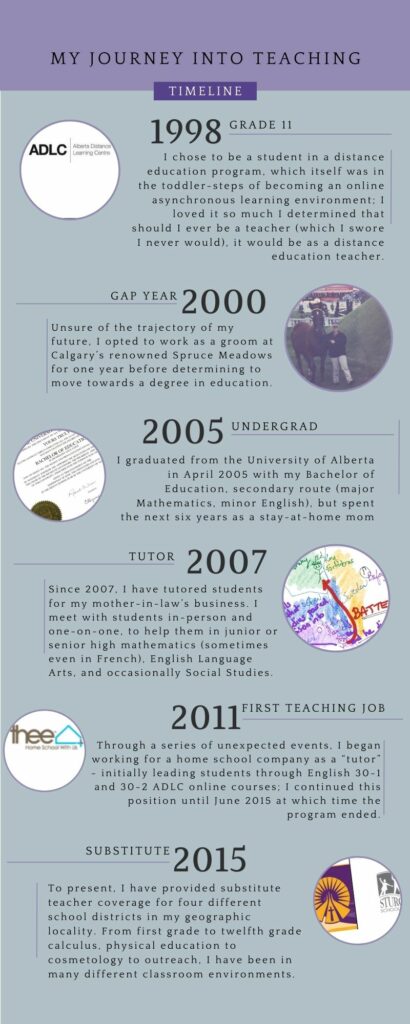

Several months ago, I was talking with my mom and somehow ended up in a conversational review of my life, beginning from the week I finished high school to present day. The conclusion: mostly, it’s chaos. My observation to my mother, however, was that despite the evidence, I continue to expect that life is going to go back to normal (read: easy) tomorrow (or next week/month/year). After laughing at the asininity of that purview, we decided that the most important takeaway is that I need to adjust my expectations (that life should be “normal” most of the time) to more accurately reflect my experience (sit deep, heels down, and hang on, because it’s a wild ride on a more-or-less continual basis)!

Thanks to the tumult of my most recent career adventure, I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on my teaching experiences, and noticing a similar kind of dichotomy there. Taken holistically, I have over a dozen years of experience, and may even be tempted to claim expertise; in light of a traditional classroom context, I’d place myself on a level playing field with a first-year teacher.

Much of my experience comes in settings where courses were already fully designed and (for the most part) skilfully developed for asynchronous online learning. As I have become more familiar with some of the theories of instructional design through research for my other M.Ed. courses, I am recognizing that cognitive load theory has been utilized in their structure and organization. Their content has also been made to align with the curricular outcomes of Alberta’s Program of Studies, and assessments (both formative and summative) are provided as an integral component of the courses.

When coupled with intentional, regularly scheduled synchronous online sessions (as was the case for my years with THEE), the task of my teaching was to create and build relationships with and among students, to support and clarify their understanding, and to provide structure and pacing through the course. Since the instructional material was already fully prepared, and learners were expected to work through the majority of the content on their own, I had the benefit of being able to preview the lessons scheduled for a given week, and highlighting the key components of these in our live sessions. I also used this time to encourage students to ask questions about content that challenged them and to share questions they’d gotten stuck on or were confused about, and invited students to collaborate and chime in with their insights as I guided the class through any remedial instruction or a demonstration of problem solving. In this environment, I was able to spend a lot of time simply reaching students where they were simply because if one student asked a question, I demonstrated the solution through soliciting input from others by asking mediational and leading questions.

In the online synchronous environment, I made use of the whiteboard, the chat features, mics and webcams, screen sharing and particularly the host controls (such as managing student chat abilities and microphone privileges). Since classes ran on a dedicated link (much like our Zoom sessions), I tried to make sure the whiteboard was populated with interesting or humours content prior to the start of class. On the occasions when I neglected to do this, students would often decorate the whiteboard themselves, which I both allowed and appreciated for the community-building effect it provided.

In this environment, one of the greatest differences compared with face-to-face settings is the utter absence of “classroom management” kinds of issues. Given the extensive host controls, I was able to manage students’ chat functionality; if ever a student was wildly off topic or persisted in typing messages which were distracting or rude, I could simply remove that student’s ability to chat to anyone but myself. Conversely, one of the largest challenges in the online environment is getting students to buy in and be comfortable enough to answer a question via mic, and to run their web cams. Technical issues contributed to this as well; many students were in rural areas and had less than stellar internet connections, which meant that if they ran their webcams along with the rest of the class, the quality of the live session would be compromised to a state of absolute uselessness. Therefore, I often allowed students to leave their cameras off, with the expectation that they would turn it on when speaking via mic.

A lot of my teaching experiences have been in online and fully asynchronous settings, and the removal of the synchronous aspects has a significant impact on the learning environment. In these situations, some of the most effective teachers I know are the ones who engage the students continually and directly through the use of an introductory email which include detailed and explicitly clear expectations, an initial phone call to follow up, and then continual stops and checks in place through the early stages of the course. The structure that is exemplified and provided in these interactions is actually what allows the students to succeed from the start, if only because it is much harder to dismiss or forget about your online course when you have a teacher who is emailing and following up with phone calls on a regular basis. I have adopted many of these elements when working in online asynchronous settings; introducing myself and attempting to provide some ways for students to feel like they know me is one of the main goals of my initial contact via email. (An example of this introduction is in this post.) The same information is shared within the course introduction. And, whenever I communicate with students (whether by phone, email or online session) I strive to provide a sense of connection and of shared human-ness along with the instruction, clarification, help, technical support, or reprimand I may be addressing. Even when dealing with difficult situations (students caught plagiarizing or cheating on an exam or who didn’t finish all of the course on time) I value being able to be forthright and emphasize the importance of growth, perseverance, personal integrity, and the need to be gracious to ourselves when we need to make a change in our trajectory despite it not being what we’d originally envisioned.

An aspect of online asynchronous learning of which I am well aware, but which I find many students are (regrettably) not, is the fact that it is a very particular and specialized kind of process, and not every person thrives in that environment. What I deeply respect is when a school operating this kind of program is upfront and clear in the expectations and structure which students will need to be successful. I feel especially passionate about this, having been a student of an online program in the eleventh grade, and working in this capacity for many years, and also because I’ve been the parent to three children in an online (though synchronous) program. In fact, I have saved multiple different written explanations (as Gmail email templates, or as Keep notes, or as PDF files) which highlight the kinds of skills, attitudes, habits, and realistic expectations that must be embraced if a student is to be successful in the online world.

These situations have been the ideal; I have also struggled through some settings which have been significantly less so, due to either having sub-par online courses (and not enough time or understanding from administrators to make adjustments and improvements, nor any professional development support to that end) or having to create online courses from scratch (while simultaneously “teaching” asynchronously). In these cases, the time required to connect with students and families and provide the support needed to engage them in the online environment was utterly overtaken by the time spent editing and fixing, or creating, course content. On the one hand, if I did not reach out to communicate with students, they were much more likely to simply not do any school work (therefore an “attendance” issue for the school); on the other, if I did not correct course content, the students would be exposed to erroneous information, and if I did not create course content, the students would have nothing at all to actually do, study, or learn. These experiences highlighted the need for meaningful parameters around the online or distributed education working conditions and assigned time to FTE employment, neither of which is currently the case in Alberta.

Absolutely polar opposite to the online education world is my work as a substitute teacher in traditional schools. I have done pull-out reading assessments and leprechaun trap planning in grade one classrooms; slogged through E.L.A. and physical education classes with ninth grade students who had zero interest in being respectful, never mind learning; spend a week teaching derivatives and the various related rules in grade twelve calculus (and yes, one student did burst into tears of utter frustration and despair near the end of the week, because I wasn’t her usual teacher); and gratefully returned upon request to an outreach high school, where the regular staff there told me that the heart and soul of the program ran on the relationships that built with the students.

Though in a face-to-face setting it may be easier to see students who are disengaged, off-task, shut down, hurting, it is not any simpler to effectuate a change in their behaviour than in online settings. But in a face-to-face environment, the effect of even one student’s off-task behaviour on the rest of the class is extremely difficult to mitigate (though this is likely exacerbated by the dynamics which exist in classrooms with substitute teachers) — a situation which is simply not a part of online settings. Unlike the online environment, being in-person removes the time to deliberate on a best course of action, but it does afford the advantage of the use of body language as a form of communication. Making eye contact, moving to be in proximity to a student, dimming the lights in the room…all of these are impossible in the online world.

And so, the dichotomy persists. As my husband described my experience to me, I am a “jack of all trades, master of none.” Yet the one unifying aspect of being a teacher, irrespective of the modality of education, is connection. It is this connection with students that feeds my soul, and if this results in even one student’s life being positively affected, then I consider myself blessed.

Post’s featured Image by G Poulsen from Pixabay

Alana

April 1, 2024 — 16:02

My beautiful sister, it is such a pleasure and blessing to read all about your career journey in life thus far. You inspire me! And, I think you must seriously consider one more career change… because with writing skills like yours, “published author” would be the cherry on top of it all!

Love you.

Alana

iamthird

April 2, 2024 — 00:00

Your lavish praise makes me smile and blush at the same time. Thanks for taking time to read a bit of my (very long) story!

Love you back.